The Balnearia series, published in the 1990s by the International Association for the Study of Ancient Baths (and now available online on this very site), contained a ‘Help!!!’ section in which scholars working on baths and intrigued by some unusual material or looking for comparanda could ask the subscribers (mainly other ancient baths experts) for their opinion. It is therefore fitting that one of the first joint actions of the BATH Network has been to answer such a request for information, received from Prof. Dominic Powlesland of the Landscape Research Centre (LRC).

The mysterious element is an unusual brick illustrated on a plate showcasing the remains of a bath building discovered in 1747 at Hovingham Hall, North Yorkshire—considered to be one of the first Roman bath buildings identified as such in Britain (the whole question of the rediscovery of Roman baths in Britain, including those of Hovingham, was tackled by Giacomo Savani in a 2019 article). After the discovery and excavation of the bathing suite, the building was soon forgotten and the memory of its location lost, presumed to have been obliterated by later developments on the estate. At least this was the assumption until archaeological research at Hovingham resumed with a series of geophysical investigations conducted by the LRC—geomagnetometry in 2008, ground-penetrating radar in 2013—that confirmed that the remains of the baths still survived a meter below ground.

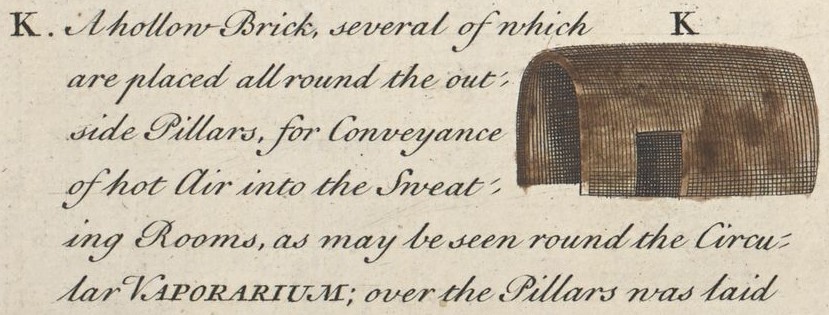

The 1747 plate (author: George Vertue) showing the plan and a mosaic of the Roman baths discovered at Hovingham. The brick in question is element K on the left (Society of Antiquaries, Prints and Drawings 1750, p. 51).

Remains the brick with an unusual shape (item K on the plate), described as ‘A hollow Brick, several of which are placed all round the outside pillars, for Conveyance of hot Air into the Sweating Rooms, as may be seen round the Circular Vaporarium’. From its representation on the picture, the brick is hollow with a deep U shape, open at both short ends, with a rectangular cut-out along the long edges (only one is visible but there was presumably another cut-out along the opposite edge). The brown colour of the brick on the original plate, the same colour as that used for the ‘pillars built of brick’ (item H), which are to be identified as the pilae of the hypocaust, confirms item K was made of baked clay. No scale is provided and no dimensions given for the brick. Based on the drawing, the cut-out is roughly a fifth of the brick’s length and a bit less than half its height; the back end of the brick also seems slightly smaller than its front end, which may be due to the perspective or is intended to suggest the brick actually had a slight tapering.

Several details about these bricks (in the plural form now, because there were more than one) are unusual, besides their shape. Their attributed function—‘for the conveyance of hot air’—immediately brings to mind a function of tubulus, but no tubuli of similar shape are known from baths around the empire. They are found ‘all round the outside pillars’, which are naturally the pilae (item H), and we know they were present at least in the ‘Circular Vaporarium’, easily identified as the single circular room (diameter c. 9.5 feet or almost 3 m) of the bath building whose plan is also illustrated on the 1747 plate. Most pilae shown on the plan are set according to the usual grid pattern (apparently distant 0.45 m centre-to-centre, which suggest they were covered by sesquipedales; the bricks of the pilae themselves are 9 inches or c. 22.5 cm on the side), apart from five pilae in the circular room that break this alignment and are set against the wall of the room. The ‘outside’ pilae could be understood as those pilae that stand against the walls of the heated rooms (in the circular room but also in the bottom left hand side room on the plan), but assuming our brick K was part of a wall heating system, the expression ‘outside pillars’ is more likely referring to the alignment of pilae closest to (but not necessarily against) the walls. Yet the presence of our bricks is only confirmed in the circular room, which seemed to have been directly heated by two furnaces coming from the left (item G, ‘Flews, for conveyance of warm Air to the Sweating Rooms’; their notable length, their position alongside each other, and the fact that they both heated the same room is also unusual). As these are the only furnaces indicated on the plan, the circular room was surely the hottest room of the baths, and a wall heating system would have contributed to maintaining this high heat in the room.

If, as suggested by the description of their function and location, they indeed carried hot air in the walls, it remains that their shape renders them fairly unpractical when compared to traditional parallelepipedal tubuli. To convey hot air, they had to be set vertically and the open long side of the bricks needs to be closed one way or another. At least three options are possible: 1) the open side was facing towards the wall; 2) the open side received the convex end of another brick; 3) the open side faced the open side of another brick, thus turning those two pieces into a larger, oblong hollow brick. Assuming there was indeed a cut-out along both long edges, option 1) is most likely: in this scenario, the rectangular cut-outs would be in correspondence with each other, thus making all the flues communicate with each other like standard tubuli or Romano-British box-flue tiles. In options 2) and 3), the rectangular openings would face the wall and the plaster lining, making them useless to the heating process—but they may still have served to fix the brick to the wall via nails or some other device.

Three propositions of the way bricks K may have been set up against in the bathing suite to heat the walls. This assumes that the entire wall was lined with these bricks, but it is also possible that only a few vertical flues were used (© BATH network).

Why, then, use such bricks for the wall heating system? In terms of production, like imbrices—to which they are formally quite similar—they were probably made by applying a slab of clay on a solid core, and the cut-outs were added later. If they were produced intentionally to be used as wall heating devices, they would be a unicum in Britain, a “D-shaped half-box tile” (as mentioned in Savani 2019, 34). Yet if so, we may wonder why the manufacturers did not go for more traditional rectangular tubuli, or box-flue tiles as they are usually called in Britain. The impracticalities of their application on the walls could instead suggest they had originally been produced for a different purpose and then reused in the bathhouse. Their shape somewhat recalls imbrices, but their depth and the presence of cutout(s) remains unexplained.

We put the question to our colleague Tim Clerbaut, from Ghent University and expert in ceramic building material, who pointed out two other examples of bricks, from Vindonissa (Switzerland) and Canterbury (UK), that shared strong similarities with the Hovingham bricks: an elongated U-shape, although shallower, and cut-outs along the long edges (one or two on each side). The Vindonissa brick, found in a reused context alongside many standard imbrices and unusual hollow bricks for vaulting, was slightly longer than 42 cm and wider than 20 cm, and was interpreted as a ridge tile used on pitched roofs to cover the junction of the uppermost rows of tegulae, with the flanges of the tegulae fitting into the cut-outs. If the Hovingham brick had similar dimensions, it could have originally served the same purpose, and have been reused for the wall heating—although that would raise the question of the number of such bricks available, and how much of the surface of the walls in the heated rooms they covered, but perhaps regular imbrices could have been used as well to the expense of the heat circulating from one flue to the next. The second example, from Canterbury, raises more questions than it answers: although it had similar dimensions (40 cm long, 10 cm high and 19 cm wide tapering to 18 on the other end), the presence of two cut-outs on each long side means it could not have worked as a ridge tile since the position of the cut-outs did not allow the regular spacing necessary for the flanges of tegulae; instead, it is deemed to have had a special use in the kiln where it was found.

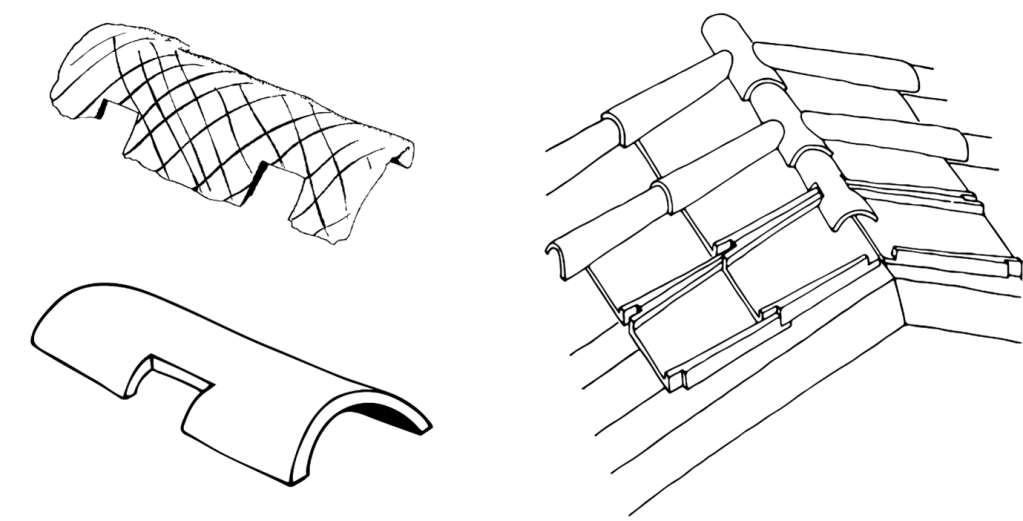

The other two bricks similar to the Hovingham example, from Canterbury (top L) and Vindonissa (bottom L). The drawing on the right shows the way the brick from Vindonissa may have been used in the roofing system, as a ridge tile on the pitched roof (adapted by author from: top L: Brodribb 1987, fig. 46; bottom L and R: Gerster 1976, fig. p. 114).

In conclusion, this leaves us with an unusually-shaped brick used for heating the walls of a round chamber in a bathhouse. This type of brick is likely to have been originally produced for a different purpose, perhaps to cover a roof ridge and keep the occupants of the building dry; instead, it finished its life cycle to keep them warm. If poetry and ancient industrial baked clay ever went together, this brick is an ode to the creativity of the Romano-British manufacturers of ceramic building materials and to their resourcefulness in adapting to local needs, sometimes by developing bespoke products, sometimes with the means at hand.

BATH Network

Redaction: KB. Contributions: GS, SM, AK. Thanks to Dominik Powlesland (Landscape Research Centre) for setting us up with this riddle, and to Tim Clerbaut (Ghent University) for sharing his knowledge of unusual bricks in the NW provinces.

Further reading / literature used in writing this post

On the rediscovery of the baths at Hovingham during excavations led by Dominik Powlesland and the Landscape Research Centre, see the LRC blog. Savani 2019 investigated the rediscovery of Roman baths in Britain. Brodribb 1987 is still a reference on the variety of use of brick and tile in the Roman world and, alongside Degbomont 1984, shows the wide range of use of such materials in bathing contexts. Lancaster 2015 is a more recent and wide-ranging assessment of (mostly brick) vaulting in the Roman world, showcasing the variety of CBM production. The two comparanda from Canterbury and Vindonissa can be found in Brodribb 1987, p. 97 and Gerster 1976, respectively.

To quote this post

BATH Network (2024), What’s in a brick? Unusual ceramic building materials in a bath of Roman Britain, Consulted INSERT DATE, <www.ancientbaths.com/2024/05/01/whats-in-a-brick-unusual-ceramic-building-materials-in-a-bath-of-roman-britain/>

Leave a comment