The ancient city of Tarraco (modern-day Tarragona) was the capital of the largest province of the Roman Empire, known as Hispania citerior, and later as Tarraconensis. Its significance is evident in the vast array of archaeological remains, including architectural structures related to public buildings, where numerous sculptures have been discovered. Recent research on the Roman sculptures of Tarragona, conducted as part of a doctoral thesis, has led to the publication of a volume in the Corpus Signorum Imperii Romani, which is scheduled for forthcoming release. (Ruiz 2025). This study has provided an opportunity to examine the statuary programs of both public and private Roman buildings in Tarraco, such as the baths.

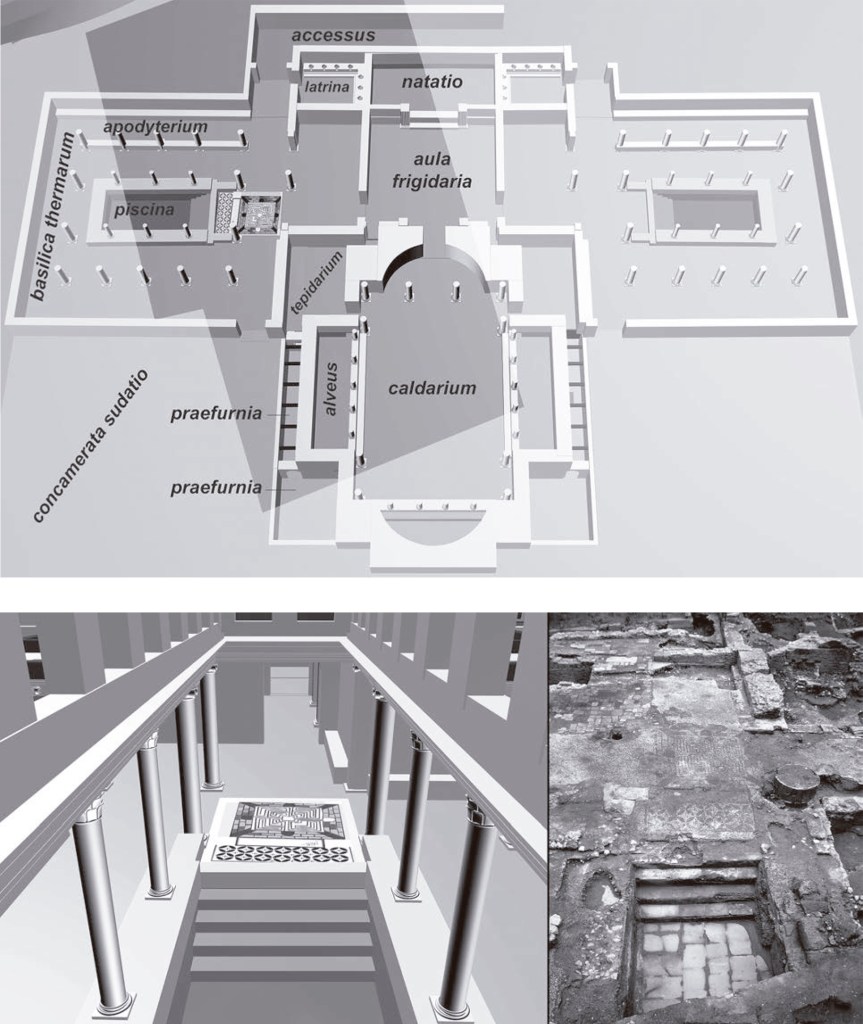

In the residential area near the forum and theatre, there were several public baths (Macias, 2020; Pavía Page 2021, 80–91) (Fig. 1). However, due to the challenging conditions under which urban archaeology has developed in this area, these buildings are not well understood. Among the remains of public baths found in the city, a notable bathhouse stands close to the ancient Roman port (Fig. 2). This building was constructed at the end of the 2nd century AD, or more likely in the 3rd century AD (Macias 2020, 286–288, figs 2–4; Pavía Page 2021, 80–85, fig. 23).

The architectural remains of this bath complex were discovered in 1976. That year, several statue fragments were found inside an apsidal room with a mosaic floor. These fragments belong to a larger-than-life statue of Apollo (Koppel 1985a, 99–100, no. 141, pl. 61; Koppel 2004a, 98–99, figs 98–101; Ruiz 2024, fig. 5; Ruiz 2025, no. 287). The statue depicts the nude deity, accompanied by a tripod with a snake, symbolizing his role as an oracle in the Delphic tradition. Preserved fragments include both legs, parts of the tripod, the snake, and the base with feet (Fig. 3).

The sculpture is crafted from coarse to very coarse white-grey marble with bluish-grey specks and veins, and a yellow patina, exhibiting high translucency. A petrographic analysis concluded that this marble came from Paros (Mayer & Álvarez 1985, 188, note 13, no. 1120). The marble surface is polished on the skin areas, as observed on all the preserved fragments.

The right leg, measuring 28 cm in height, includes the lower half of the thigh, the knee, and the beginning of the calf. It corresponds to the leg on which the figure was standing. The left leg, preserved up to a length of 59.5 cm, is very flexed and raised, indicating that its foot rested on a higher surface. The most significant fragment is the oval plinth, on which are the bare feet of the figure, which was standing on its right leg. The left foot was positioned atop a bull’s head. To the left of the feet is a support in the form of a Delphic tripod with an omphalos, with moulded legs resting on feline claws, around which a snake coils. Additionally, several other fragments of this tripod, including a leg, crossbars, and the coiled body of the reptile, have been preserved.

The statue was of high stylistic quality, evident in its detailed representation of anatomical features and musculature. The fragmented statue of the sculpture has distorted its excellent craftsmanship. Based on stylistic comparisons with similar examples, the sculpture is dated to the 2nd century AD, and more specifically to the Hadrianic period. It was probably imported, created by a skilled artisan, perhaps Greek, working in a workshop in the eastern Mediterranean or near Rome. This is not only due to the technical quality but also to the faithful reproduction of the Greek model, both of which are characteristic of the craftsmanship of the Eastern and metropolitan workshops (Pensabene 2006; Ruiz forthcoming).

Despite its fragmentary condition, the presence of the Delphic tripod and the omphalos confirms the identification of the statue as an image of Apollo. Due to the position of the limbs, it belongs to a statuary type known as “Lykeios” (LIMC II [1984] s.v. Apollon, 193–194, no. 39, pl. 184; LIMC II [1984] s.v. Apollon/Apollo, 379–380, no. 54, pl. 302; Nagele 1984; Schröder 1986; Vorster 1993, 58–60, no. 23, figs 100–113; Grassinger 2015, 245–248, fig. 6), which depicts the deity in the nude, standing in a relaxed, frontal position. One of the best preserved replicas is in the Louvre Museum. The right arm was raised and placed over the head, while the left arm was bent forward, likely holding a bow. Some scholars suggest that the Greek original, copied in most Roman versions, rested its left arm on the tripod or a tree trunk (Nagele 1984, 100), while other researchers propose that this posture is a Roman variant, and the original stood in front of a column (Schröder 1986, 169–170). The term “Lykeios” comes from ancient sources (Lucian Anarch. 7; Schröder 1986, 167, note 4), which mention that the Greek original stood in the Lykeion of Athens. This original has been dated to the third quarter of the 4th century BC, and some scholars attribute its creation to Praxiteles, though this theory is not universally accepted.

The statue from Tarraco differs from other replicas of the same statuary type due to the presence of the bull’s head, leading to the theory that it is a syncretic image of Apollo and Mithras. However, this hypothesis lacks comparative examples. Moreover, its dating to the early 2nd century AD predates the construction of the baths where it was found, suggesting that it was relocated from an earlier building and reused in the baths. Its original purpose remains unknown, but within the baths, it was likely related to the therapeutic function of bathing.

During later excavations in 1998, additional, highly deteriorated statue fragments were found (Koppel 2004a, 98, figs 96–97; Ruiz 2025, nos 288–297). Initially, these fragments were unequivocally attribute to the baths’ decoration (Koppel 2004a). However, the review of the excavation records revealed that these fragments come from uneven stratigraphic levels, suggesting that they had been moved and dumped from other locations (Ruiz 2025).

The sculptural remains from the baths of Tarraco are only partially understood, making it difficult to determine their precise meaning. Nevertheless, the Apollo statue is a valuable piece of evidence. It likely belonged to a broader statuary program that, as seen throughout the Roman world (Manderscheid 1981; Koppel 2004b), conveyed messages relating to the therapeutic and recreational functions of these buildings. Moreover, such sculptures of deities contributed to a mystical atmosphere in the baths.

Julio C. Ruiz, Autonomous University of Barcelona (UAB) and Rovira i Virgili University of Tarragona

julioruiz92@hotmail.es

https://independent.academia.edu/RuizJulioC

References

Grassinger, D. (2015) Apollo und Bacchus, die ‘Bild-schönen’ Jünglige. In Boschung, D. and Schäfer, A. (eds.), Römische Götterbilder der mittleren und späten Kaiserzeit (Morphomata, 22). Paderborn: Wilhelm Fink, 235-257.

Koppel, E. M. (1985) Die römischen Skulpturen von Tarraco (Madrider Forschungen, 25). Berlin: De Gruyter.

Koppel, E. M. (2004a) L’escultura. In Macias, J. M. (ed.), Les termes públiques de l’àrea portuària de Tàrraco. Carrer Sant Miquel de Tarragona (Documenta, 2). Tarragona: ICAC, 97-100.

Koppel, E. M. (2004b) La decoración escultórica de las termas en Hispania. In Nogales, Tr. and Gonçalves, L. J. (coords.), Actas de la IV Reunión sobre Escultura romana en Hispania / IV Reunião sobre Escultura romana na Hispânia. Faculdade de Belas-Artes de Lisboa, Universidade de Lisboa, 7, 8 & 9 fevereiro-2002. Lisboa: Ministerio de Cultura, 339-366.

LIMC = Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae, Bandem I-VIII. Zürich / München / Düsseldorf: Artemis, 1981-1997.

Macias, J. M. (2020) Las termas públicas de Tarraco: una investigación pendiente. In Noguera, J. M., García-Entero, V., and Pavía, M. (coords.), Termas públicas de Hispania (Spal Monografías Arqueología, XXXIII). Sevilla: Universidad de Murcia / Universidad de Sevilla, 283-291.

Manderscheid, H. (1981) Die Skulpturenausstattung der kaiserzeitlichen Thermenanlagen (Monumenta Artis Romanae, XV). Berlin: Mann.

Mayer, M.; Àlvarez, A. (1985) Le marbre grec comme indice pour les pièces sculptoriques grecques ou de tradition grecque en Espagne. In XII Congrès International d’Archéologie, Athènes 1983. Atenas: Hypourgeio Politismou kai Epistemon, 184-190, pls. 31-32.

Nagele, M. (1984) Zum Typus des Apollon Lykeios. Jahreshefte des Österreichischen Archäologischen Institutes in Wien 55, 77-105.

Pavía Page, M. (2021) Thermae Hispaniae citerioris. Análisis arquitectónico y tipológico de los complejos termales públicos y urbanos de Hispania citerior (Anejos de Archivo Español de Arqueología, XC). Madrid: CSIC.

Pensabene, P. (2006) Mármoles y talleres en la Bética y otras áreas de la Hispania romana. In Vaquerizo, D. and Murillo, J. F. (eds.), El concepto de lo provincial en el mundo antiguo. Homenaje a la Prof. Pilar León II. Córdoba: Universidad de Córdoba, 103-142.

Ruiz, J. C. (2024) L’arredo statuario degli edifici pubblici di Tarraco (Hispania citerior). In Cristilli, A., Di Luca, G., Gonfloni, A., Capra, E. S., and Pontuali, M. (eds.), Experiencing the Landscape in Antiquity 3. Oxford: BAR Publishing, 307-312.

Ruiz, J. C. (2025) Corpus Signorum Imperii Romani – España. Tarragona (conventus Tarraconensis, Hispania citerior). Murcia.

Ruiz, J. C. (forthcoming) Roman Marble Statues from Tarraco (Hispania citerior): imports and local production. In Landstätter, L., Prochaska, W., and Anevlavi, V. (eds.), ASMOSIA XIII. 13th International Conference. Association for the Study of Marble and Other Stones in Antiquity. 19-24 September 2022, Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna. Vienna.

Schröder, St. F. (1986) Der Apollon Lykeios und die attische Ephebie des 4. Jhs. Mitteilungen des Deutsches Archäologischen Instituts. Athenische Abteilung 101, 166-184, pls. 33-35.

Vorster, Chr. (1993) Vatikanische Museen. Museo Gregoriano Profano ex Lateranense. Katalog der Skulpturen II,1. Römische Skulpturen des späten Hellenismus und der Kaiserzeit 1. Werke nach Vorlagen und Bildformen des 5. und 4. Jahrhunderts v. Chr. Mainz am Rhein: von Zabern.

To quote this page

Ruiz J.C. (2024), The Public Baths of Tarraco (Hispania citerior): The Sculptural Remains, consulted on INSERT DATE, <https://ancientbaths.com/2024/10/01/ruiz-the-public-baths-of-tarraco/>

Leave a comment