by Yang Mei

The following post is a summary of the Yang Mei’s ongoing doctoral thesis, carried out within the Doctoral Program in Ancient and Medieval Science at the Autonomous University of Barcelona. All opinions expressed are those of the author.

When we mention the ancient Roman baths, we can’t help but think of the grand imperial baths of Rome. However, in the Pyrenees, far from the capital of the Roman Empire, there are also many remains of ancient Roman baths. The North Baths of the Roman city of Lugdunum Convenarum is one such example.

Lugdunum Convenarum is now located in the small town of Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges, close to the northern foot of the Pyrenees. The city was established by Pompeius Magnus around 72 BC to control the mountain road from Spain to Gaul (May 1996).

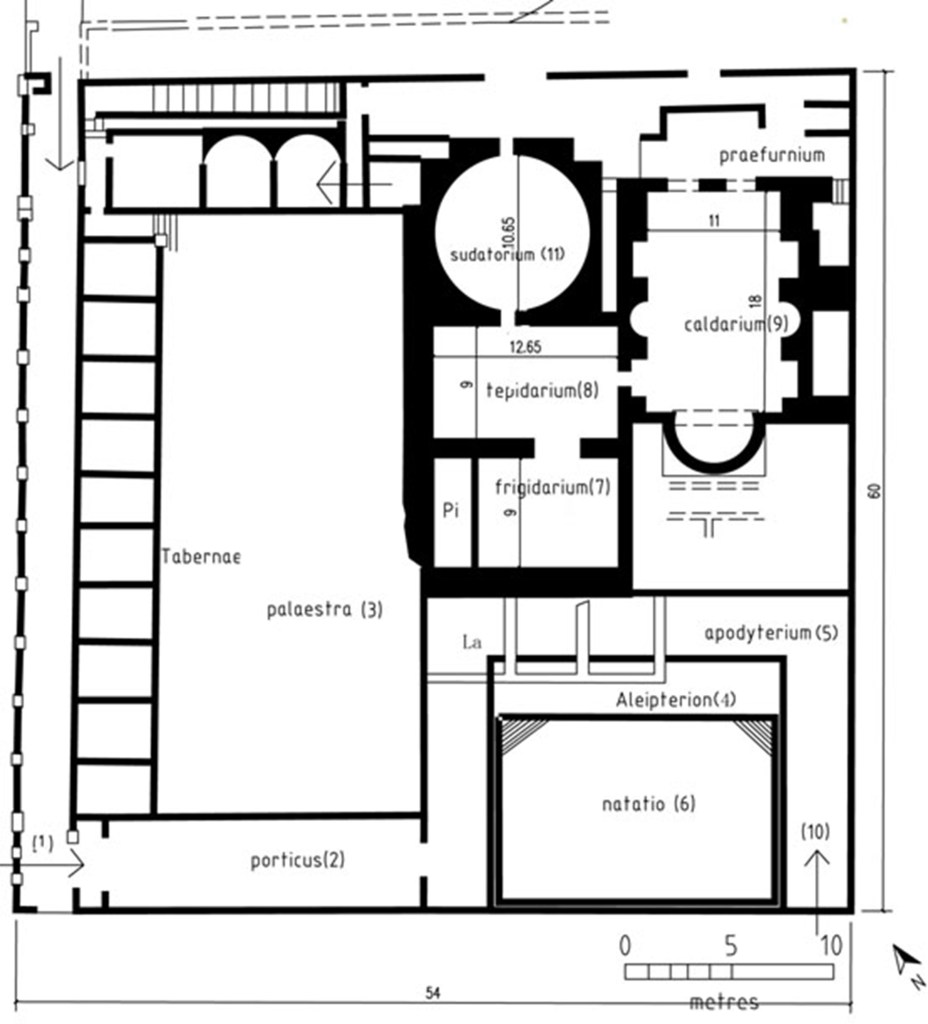

The North Baths are situated to the northwest of the city’s forum. They are 60 meters long from east to west and approximately 54 meters long from north to south. Their plan is complex, and they have gone through multiple phases of reconstruction and renovation. The earliest architectural elements may be traced back to the mid-1st century AD, while they reached their final form in the early 2nd century AD. Most of the information on the baths comes from Simon Esmonde Cleary’s publication on the city (Esmonde Cleary 2008).

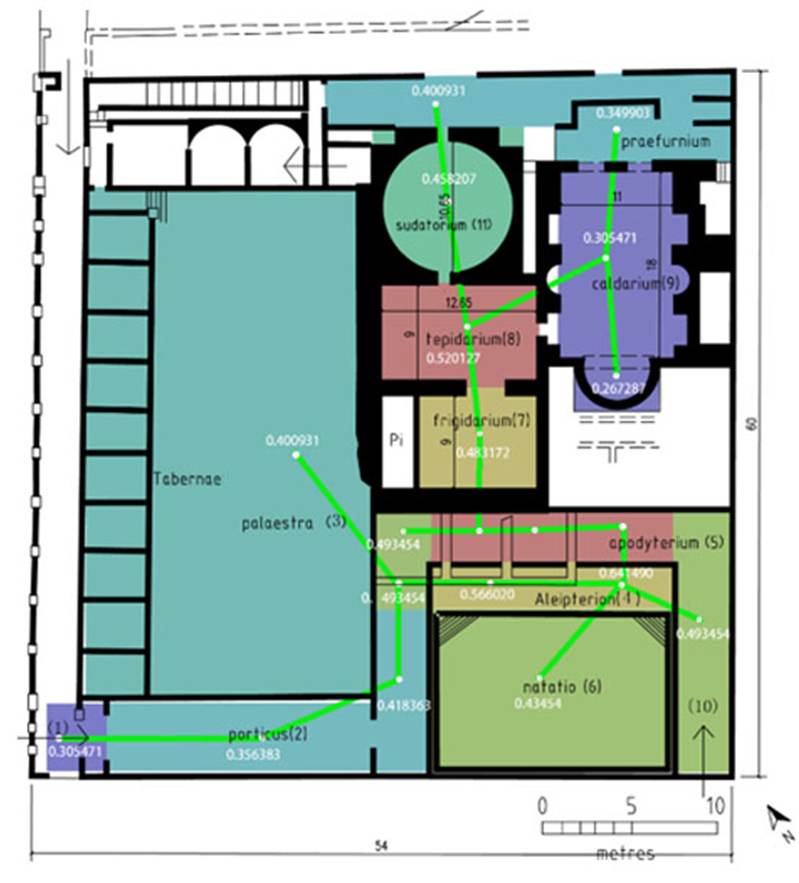

Space syntax is often used by architects and planners as a computational means to analyse the floor plan of buildings(Hillier 1996; Hillier & Iida 2005). This article uses it as a method to explore the design of the plan of the ancient Roman baths. The plan of the North Baths is a typical angular row type plan according to Nielsen’s classification (Krencker & Krüger 1929, 177–181; Nielsen 1990, 111) (Fig. 2). It has a built area of ca. 1700 square meters and features a hot room (caldarium), a sweat room (sudatorium), a tepid room (tepidarium) and a cold room (frigidarium). On the west side, a large palaestra of 3240 square meters and a row of shops (tabernae) can also be identified, indicating that this building also had social and commercial functions (Esmonde Cleary 2008).

The space syntax analysis of the North Baths provides us with a tree-like topological map map reaching a depth of up to 9 levels, with three architectural spaces (nodes 2, 4, and 8) acting as critical nodes (Fig. 2). This pattern suggests that access within the complex was tightly regulated. This layout, in which the bathers progressed from one room to the next, is not accidental but reflects a standardisation of the bathing itinerary. Visitors needed to pass through multiple spaces in sequence before entering the more secluded, or core, areas. The combination of the asymmetrical layout and linear paths deepens the sense of hierarchy and the guidance of movement in the internal space, enabling people to be ‘guided’ or even ‘regulated’ in their movement throughout these spaces. This held significant symbolic meaning in ancient Roman society, where the arrangement of rooms within public baths embodied Roman society’s emphasis on order and hierarchy.

In space syntax analysis, connectivity, integration , and visibility graph analysis (VGA) serve as key quantitative indicators, visually representing spatial connections and function through colour-coded diagrams.

‘Connectivity’ measures the number of nodes directly linked to a given node, reflecting local accessibility. Warm colours (e.g., red or orange) denote high connectivity, identifying hubs with many direct links. Cool colours (e.g., blue or green) indicate low connectivity, signifying relative isolation (Fig. 3). Higher connectivity typically correlates with better accessibility, increased usage, and greater potential for interaction (Hillier 1996).

Conversely, ‘integration’ quantifies global path efficiency across the entire architectural space system. Warm colours represent high integration, corresponding to areas with shorter, more efficient paths. Cool colours denote low integration, reflecting areas reached via longer paths, and with poorer accessibility (Fig. 4).

The main function of VGA is to analyse ‘visibility’ in space, which illustrates how much and how far the users of the space could see, and how this visual connectivity affected the use of space (Fig. 5).

Archaeological evidence suggests that visitors primarily entered the baths from the southwest entrance (Room 1). Passing through the first architectural node (Room 2), they proceeded along the western side of the swimming pool to reach the second architectural node (Room 5) (Fig. 2).

Node 4, located to the north of the swimming pool, consisted of a series of interconnected rooms (rooms 4, 5 and 6). This compact space of 26 m² concentrated several functions. Room 5 led to the changing area and provided access to the frigidarium; room 4 served for oiling and as a waiting space (Fig. 1).

Before entering the large natatio (room 6), people would pause in room 5 to change clothes, select their preferred form of bathing — that could include oiling or swimming beforehand—and engage in social interaction. Thus, this space functioned not only as a preparatory and transitional zone but also as a key venue for interpersonal exchange. This space scores the highest in terms of spatial integration, indicating its central position within the baths (Fig. 4). The high degree of integration underscores its dual role as both the starting point and the convergence point of the bathing sequence, making it the principal hub for gathering and social interaction.

In this sense, compared with Node 1 at the entrance, Node 2 may be regarded as the true ‘social stage entrance’—a threshold where individuals moved from private actions into the collective order of public life (Stöger 2007).

The VGA results for Node 4 (room 4) highlight its importance and indicate it was the second strongest visual focus of the baths after the tepidarium (Fig. 5). Given the Roman concern with sequence and order in bath design, Roman architects may have deliberately emphasised Node 4 as the first visual and functional focal point. This design strategy prepared bathers for the transition toward Node 8 (room 8), where the space expands dramatically, reinforcing its public character and promoting social interaction therein.

Node 8 (room 8), the tepidarium, exhibits the highest connectivity, functioning as the central transition hub that linked the hot and cold rooms (Fig. 4). Compared to other bathing spaces (such as the caldarium, sudatorium, or frigidarium), the tepidarium may have served more frequently as a social venue. As a space connected to multiple rooms, it facilitated the gradual adaptation of bathers from cooler to warmer environments while providing opportunities for rest and interaction. The VGA analysis further underscores its significance: Room 8 displays the warmest coloration, indicating its wide visual field and strong influence on adjacent rooms. It thus emerges as the primary visual and functional focus of the entire complex, representing the climax of the architectural sequence (Stöger 2014).

From the tepidarium, bathers could then move into the sudatorium, proceed to the hot bath, or return via the frigidarium to the pool and the oiling room. Beyond this point, the spatial sequence became increasingly private, ordered, and singular in function.

Therefore, this bath complex functioned simultaneously as a place for bathing and social interaction and, at a metaphorical level, as a representative of power and order: as the bathers penetrated more deeply inside the building, their movements were more restricted. This type of spatial organisation is a direct manifestation of how the Roman Empire encoded hierarchical order and social norms in architecture.

The North Baths replicated bath designs that were already popular in various cities of the Empire. Both the architectural layout of the building and the behavioural cues found within it followed Roman standards. This indicates that the commissioners had fully accepted Roman urban culture and regarded baths as a necessary component of a civilised life. Other inscriptions unearthed in Lugdunum Convenarum mention a monument to the victory of Augustus and a temple dedicated to the worship of Rome and the emperor (Esmonde Cleary 2008). This implies that the construction of public works such as the North Baths was likely accompanied by political acts of loyalty to the imperial family: members of the local elite built not only the baths, but also erected monuments and temples to praise the emperor’s achievements and show their loyalty (Esmonde Cleary 2008, 62–68). In other words, the existence of the North Baths itself was a symbol of the legitimacy of Roman rule, reflecting local support for the central government.

In the Pyrenees region, many ancient Roman baths have been excavated, for example, at Labitolosa, Los Bañales, etc. Compared with other ancient Roman baths in the region, the North Baths of Lugdunum Convenarum are on a grand scale, and their plan shows a distinct spatial zoning and hierarchical order (Fig. 1).

After the Sertorian War (80–72 BC), Pompey settled some veterans, the Convenae tribe, and captives in Lugdunum Convenarum. Among such a diverse population, establishing Roman-style public baths helped shape a common lifestyle. Residents gradually identified with Roman concepts of social order and hygiene by participating in Roman bathing customs.

By their architectural layout, urban role, cultural significance, and power connection, the North Baths of Lugdunum Convenarum were a political microcosm of urban life in the Roman Empire. They included almost all the typical architectural elements of the Roman public baths and reflected the Empire’s politics, society, and culture through a single building. They had a clearly hierarchical spatial configuration, symbolising the organisational principles of Roman society. They were in a key area of the city and played a dual role. Their practical function, providing a space for relaxation and leisure, combined with the magnificent decoration and orderly architectural design, served both the purpose of uniting the local citizens and showcasing the presence of Rome. The construction and evolution of baths attested to the spread and uptake of Roman culture in the provinces. Their existence relied on the political, economic, and cultural support of the Empire as well as the economic dedication of members of the local elite, which reflected the cooperative model of in-depth collaboration between local elites and active promotion of cultural and political assimilation when Rome ruled the western provinces.

From the example of the North Baths, we can get a glimpse of how ancient Roman politics permeated daily urban life—even in the ruins of a bath building far away in the Pyrenees, the scent of Roman power and civilisation still lingers.

Mei Yang, Autonomous University of Barcelona

mei.yang2@autonoma.cat

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-9731-0635

References

Esmonde Cleary, A.S. (2008), Rome in the Pyrenees: Lugdunum and the convenae from the first century B.C. to the seventh century A.D., London – New York.

Hillier, B. (1996). Space is the machine: A configurational theory of architecture, Cambridge.

Hillier, B. & S. Iida (2005), Network and psychological effects in urban movement, in A.G. Cohn & D.M. Mark (eds), Spatial Information Theory, International Conference COSIT 2005, 475–490. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/11556114_30

Krencker, D., & E. Krüger (1929), Die Trierer Kaiserthermen: Ausgrabungsbericht und grundsätzliche Untersuchungen römischer Thermen, Augsburg.

May, R. (1996), Lugdunum Convenarum. Saint-Bertrand-de-Comminges, Lyon.

Nielsen, I. (1990), Thermae et balnea: The architecture and cultural history of Roman public baths, Aarhus.

Stöger, H. (2007), Roman Ostia: Space Syntax and the Domestication of Space, in Layers of perception: proceedings of the 35th CAA Conference, Berlin, Germany, April 2-6, 2007, Bonn, 322–327.

Stöger, H. (2014), The Spatial Signature of an Insula Neighbourhood of Roman Ostia, in E. Paliou, U. Liebewirth & S. Polla, Spatial Analysis and Social Spaces: Interdisciplinary Approaches to the Interpretation of Prehistoric and Historic Built Environments, Berlin – Boston, 297–316.

To quote this page

Yang, M. (2025), Power and Order in Roman Bath Architecture: A Spatial Syntactic Interpretation of Lugdunum Convenarum, the North Baths – thesis summary, <https://ancientbaths.com/2025/11/10/yang-thesis-power-and-order-in-roman-bath-architecture/>

Leave a comment